I'm going through a tough time in my life right now.

A year ago, I had a dead-end job. I wasn't utilizing my bachelor's degree in physics, mostly because the proper thing to do with a bachelor's degree in physics is continue to graduate school and get a master's degree or, likely, doctorate. Of course, I had been in graduate school, and dropped out for various reasons, among them severe depression and a dying interest in academia. I had decided I didn't want to teach and I didn't want to research. Getting a Ph.D. in physics not only requires both but commonly leads to one or the other. There are industry jobs as well, but I didn't have one in mind. So I had left school, and I was working, and then a year ago I decided to go back to school in another subject. For the past year, I've been studying computer science instead, with the aim of getting a master's degree in the new subject. I was confident, at first, but my present transition from undergraduate computer science coursework (in which I did extremely well) to graduate computer science coursework (which somehow isn't what I expected) is making me doubt that I can pull this off. If I can't, then I don't know what I'll do. I'm already old. My depression is coming back, which is causing problems in my relationship with my long-time girlfriend, which is causing more depression. It's not like I'm in need of psychological help. I've been through much worse and I survived. But it still sucks.

On top of all that, perhaps worst of all, is the most unbearable hardship I can imagine: I don't have time for video games anymore.

I certainly don't have time to be writing this. I mean, if I were really a good student, I would be studying or writing a paper right now. I'm not sure what prompted me to start writing this post, aside from a need to vent. I'm not even sure where I'm going with it. I guess I'll just go where my heart takes me. Outlines and structure be damned. I might not even proofread this.

Video games are a tremendous waste of time. That much is clear. All the thousands of hours I've spent playing video games over the past 20 or more years could have been spent doing much better things. I could have been studying more in high school to get straight As instead of that mediocre mix of As and Bs. I could have been working every summer instead of staying up all night every night with my eyes glued to a screen. Realistically, though, even if video games had never been invented, I suspect my eyes would have been glued to screen anyway. I'd have spent those endless hours watching TV, like a less nerdy version of a person who is exactly as lazy as I am. Are video games a more tremendous waste of time than any other non-athletic, non-educational form of recreation? If so, it's probably just because they're harder to put down.

Video games have been an important part of my life, whether I like it or not. A surprising number of my childhood memories come with a footnote of which game I had been playing that week. I once went sledding with my friends on the same day I played quite a bit of Star Fox 64, and now sledding reminds me of Star Fox 64. (Is that weird?) I talk about video games frequently with my siblings, but I often have to stop myself from doing so with my girlfriend and other people who don't care to hear how something in a game I played years ago might be relevant to the current topic of conversation where a more normal person might reference a TV show or a movie instead.

My girlfriend doesn't care about video games. She might even dislike them, perhaps even as much as I dislike her taste in music. It's not something we do together. I wish that would change, though. If she had a decently working computer, I'd try to get her to join me in some game she might enjoy, like Portal 2 or anything else with a learning curve appropriate for someone who hasn't been playing video games for at least two decades. Then again, maybe not. On rare occasions in the past, she has played a video game with me (or played alone as I watched), but I'm fairly sure now that she only forced herself to do so because she thought I'd be happy if she gave some of my hobbies a try. I'd love it if she actually enjoyed all the things I enjoy, but I wouldn't want her to pretend to like something for my sake. I haven't suggested video games as an activity for the two of us in a long time, and I guess that's why.

Is this a problem? Would I rather be dating a "gamer" instead? Absolutely not. I love my girlfriend far more than I love video games, and I think a mutual interest in something like video games is an stupid basis for a relationship. But that's just me. So you found the love of your life at a LAN party? That's amazing and I'm happy for you. For me, though, a shared interest in video games is neither sufficient nor necessary as a prerequisite for love. I'm not even convinced that it's a significant perk. I was briefly with one person who loved video games, and her interest in games didn't help the relationship work. I've been with my current girlfriend for much longer, and I've found that it's good to have something I can do without her anyway. (On a more cynical note, video games aren't going to remind me of her if we break up, so at least there's that.)

If we ever have children, she'll probably want to place strict limits on their use of the video games that will inevitably end up in our home, and I think I'd be okay with that. I could have used more discipline when I was younger. Now, like a tobacco addict who tells kids not to smoke, I know how addictive video games can be, and I don't think it makes me a hypocrite to say that kids shouldn't play them for 12 hours a day even though I used to do the same on a semi-regular basis. Moderation is key.

I don't think I could ever bring myself to ban video games from my future household entirely, and not just because I enjoy them immensely myself. No kid in the 21st century wants to have the weirdo parents who don't allow video games. Furthermore, video games are probably the cure for the inevitable phase of adolescence in which kids no longer want to hang out with their parents. As someone who always thought video games were cool, I would have been thrilled at any stage of my life if my mom or dad had wanted to play a video game with me. I don't think that ever happened, though.

The worst thing video games ever did to me was keep me from more frequently reading books for pleasure, but I can't really blame video games for simply being more fun. Now the shoe is on the other foot; my childhood is far behind me, and leading a productive life means I'm kept from the beloved pastime on which I spent far too much time in my youth. It hurts. But that's life.

Showing posts with label portal. Show all posts

Showing posts with label portal. Show all posts

Thursday, February 5, 2015

Friday, December 21, 2012

We're All Mass Murderers

One week ago, a guy in Connecticut went and killed 20 young children, 6 adults, and himself. If you've been anywhere but under a rock for the past seven days, you've heard all about it, so I won't elaborate. It's a tragedy.

Predictably, in an attempt to make sense of it all, the media and the politicians have come up with a list of scapegoats against which the government is now being pressured to take action. You probably see where I'm going with this. It's the usual list of suspects: gun control, school security, and violence in media — specifically, in video games.

I understand the need to throw the blame around. No one wants to admit that a catastrophe like this one is almost completely unavoidable, so we narrow down the enormous list of contributing factors to an arbitrary few which might, we think, be controlled; we don't even think about the uncontrollable factors because that's just too depressing. So we say, let's tighten security at public schools, and let's tighten restrictions on guns. No one wants to accept that such a mentally disturbed and suicidal person, hell bent on taking people with him when he dies, is going to find a way to do it — even if it's difficult to obtain a firearm, and even if it's not easy to get into the building.

Take a look at this particular shooting, for example. The guy forced his way into a school which had already taken every reasonable security measure. The doors were locked so he shot through a window to get in. Short of multiple armed guards at every entrance (a ridiculously infeasible solution), what were they missing? Metal detectors at the doors, a common placebo in a post-Columbine world, obviously don't help when someone comes in shooting everyone on sight. Maybe bullet-proof glass would have helped, but then he might have crashed his car through the doors, or used a bomb, or waited until the kids went outside for recess. The reality of the situation is that there's no way to make a school impenetrable.

Likewise, there's no realistic way to keep weapons out of the hands of dangerous people. We can try, but there's always going to be another tragedy that occurs despite whatever precautions we take. Bad people are going to get their hands on guns for as long as guns exist — which, by the way, is forever and always, because it's too late to stop them from being invented, manufactured, and sold to millions of people. I could go and steal a gun right now, from a legal gun owner, and kill a guy for no reason, and it will not have mattered what the gun laws were or how the gun's original owner obtained it.

So yeah, blame guns... but be aware that blaming guns only works if your solitary goal is to assign blame. If you actually want to get things done and solve problems, it's pointless. To use a classic (or perhaps trite but still valid) argument, even a total ban on guns would only disarm those civilians who obey the law, and murderers typically don't. Obviously, this is just an example to illustrate the futility of trying to place limits on something for which there's already a black market, and I'm aware that the goal here isn't to repeal the second amendment. Nobody whose opinion is worth a nickle actually wants to ban guns altogether, for then we'd truly be at the mercy of the thugs who still manage to get them. The sensible approach, anti-gun folks say, is to take a careful look at gun regulations and see if they need to be adjusted.

There's a lot of talk about smaller magazines, for example, but reloading isn't that hard, especially when the innocent children you're shooting aren't fighting back. In a perfect world, the ultimate goal of gun regulation would not be to make criminals kill us more slowly, but to keep guns only in the hands of law-abiding citizens. In reality, that's a pretty tough job. Everyone's a law-abiding citizen until his or her first crime, and if that first crime is mass murder then we're boned. If only real life were more like The Minority Report. If only we could know who the criminals are in advance and take away their rights accordingly. But there are some realistic precautions we can take. For example, perhaps the shooter's mother, from whom the guns were stolen, should not have been allowed to have firearms in the same house as a person who was known to be mentally ill. Although I suppose one doesn't always know when ones offspring is crazy enough to shoot up a school, dealing with mental health is probably a good place to start.

And that's what matters, really. The guy was crazy, and we might never know for sure why he did it. Yet, in looking for reason where none exists, politicians have been quick to point instead to a culture obsessed with violence — yes, the culture in which nearly all of us live healthy and functional lives without committing mass murder — and this, of course, is where video games are mentioned. After all, the shooter in Connecticut played video games, according to news reports. That's right, he played violent games, with guns in them, and that must have driven him to kill people... because, as we all know, that's a totally normal reaction to violent video games... and it's not like playing video games is totally normal behavior for an entire generation or two. (In case you missed the sarcasm, what I'm saying is that the killer's possession of violent video games is neither significant nor newsworthy, but that doesn't stop a bunch of technophobic old people from directing a large portion of the blame at the one thing they truly don't understand.)

I shouldn't need to point out that life-long exposure to war-themed, assassination-themed, murder-themed video games (and movies and books) has never given me any desire to kill a bunch of people in real life. But why not? Shouldn't I be going on a killing spree right now? I've killed so many virtual people in video games that, if they were real people, I'd be worse than Hitler. I'm a virtual mass murderer, just like everyone who ever played a first-person shooter. I grew up on shooting things. Even so, I turned out just fine, and I know a few million people who can say the same. Maybe it's because I know the difference between reality and fantasy. Maybe it's because I know the difference between right and wrong, even without the help of some religion to continually threaten me with the idea of eternal damnation. Maybe it's because I'm not mentally ill.

But hey, that doesn't really matter now; conservative politicians and sensationalist newscasters know that video games cause violence, because that's the only explanation for what happened at Sandy Hook Elementary School, right? A crazy guy played video games, and therefore video games made him crazy? Well, that's what we're supposed to believe, but I don't. If someone is evil enough or crazy enough to actually murder 26 people, he certainly doesn't need to play video games in order to get the idea of using a gun as his instrument of death. Furthermore, it's fairly obvious that people who don't play video games are vastly overestimating a first-person shooter's ability to immerse the player. Contrary to what pundits and crackpot psychologists will claim, players are aware that it's only a game and, in the absence of some crippling mental deficiency, they won't be led to believe that really killing real people with a real gun is just as fun and harmless as competing against friends in some crazy deathmatch-style game with cartoon violence and infinite lives.

The shooter played video games just like every other 20-year-old guy I know. There are reports that he was obsessed with them — that he spent all day in his basement playing Call of Duty — but if he truly had a video game addiction (and if such a thing even exists), that's more likely a symptom of his mental illness than a contributing factor. Surely we should all recognize that the act of playing Call of Duty, one of the most popular video game series of the past few years, is not a warning sign that we should hope to use in order to predict school shootings. At least, I certainly hope not. Call of Duty: Black Ops sold 5.6 million copies worldwide in a single day, and 13.7 million copies to date in the United States alone.

That's a whole lot of potential school shootings. If video games create murderers, we should all be soiling our pants and heading for the bomb shelter. Fortunately, the available data doesn't really support the idea that violent video games cause violent acts. (Some further reading here.)

But I'm not too bothered by the blind insistence (regardless of the absence of any reliable evidence) that violence in media is destroying the moral fabric of our society. That's an opinion you're allowed to have, as far as I'm concerned, though I do strongly disagree. What really bothers me is that the people making these claims just don't know anything about video games. If they had pointed solely to the most gruesomely and graphically violent first-person shooters in their quest to find something to blame, then at least their arguments would be coherent. Instead, intentionally or not, the media is once again portraying all of gaming as an amoral pastime for misanthropes, while failing to realize that some of the most popular games of the past decade — I'm looking at you, Portal — simply aren't violent at all.

Things made some sense when they singled out Call of Duty, a game which does, in fact, put players in the role of a soldier who goes around shooting people (though, more accurately, the soldier shoots enemy soldiers in a time of war). But even if they hit the nail on the head, here, I think it was blind luck, since it's pretty clear that most of the people calling for a boycott or a ban on violent games can't even tell one genre from another. Immediately after the shooting, people were so quick to blame Mass Effect — a role-playing game better known for its sex scenes than its shooting — that a mob-like raid on the game's Facebook page began before the real killer was even identified (and ended shortly thereafter).

The media also pointed to StarCraft II, a real-time strategy game, and I think this is especially ridiculous. Not only is this not a mindless murder game; it's not even a shooter. As a strategy game, it's all about resource management, map control, and positioning of troops. Furthermore, StarCraft is to Chess as Call of Duty is to beating your head against the wall. You could judge StarCraft based on the number of virtual "people" who die in a typical match — surely, that number is well into the hundreds, or even thousands — but the player isn't assuming the role of a guy with a gun. The player is the commander telling all the guys with guns where to go. Since real-time strategy games like StarCraft don't put a gun in the player's hands, the experience absolutely does not bear any resemblance to walking into a school and murdering a bunch of children, not even to the sickest mind.

So yes, the game is violent in the sense that its central theme is armed conflict, but it's an idiotic example to use if you're trying to draw some tenuous connection between a mass murder and the killer's enjoyment of interactive media. To some, I guess, the presence of any violent theme is bad enough. But most of these "violent" games, I think, aren't simply violent for the sake of eroding our children's sense of morality. The typical video game has a story, every story involves some form of conflict, the most dramatic conflicts tend to be violent, and violent conflicts in the modern world begin and end with the pull of a trigger. Want fewer war-themed games? Let's have fewer wars. It's not that we should just give up and blame human nature, but we can't expect every video game to be full of super happy rainbows and sunshine either.

Video games consistently imitate life, so even if life does imitate video games on rare occasions, you can't say that video games are the source of all our problems. And, again, it's nothing if not completely illogical to blame video games for a mass murder just because the murderer was one of a billion people who play them. (I bet he also took history classes in high school, but I'm not blaming those history teachers and their lessons about war, because there's no real correlation, let alone any evidence of causation.) There isn't even a very good reason for the news people and the politicians to pick on video games, in particular, so much more than other forms of media that supposedly glorify violence. What about movies and TV shows?

You could say that video games are special because of the level of interactivity that's missing in other forms of entertainment, but I'm beginning to doubt very much that this has anything to do with it. No, video games are special because they're the "new" thing that too many people still don't understand. Fifteen or twenty years ago, they would have blamed rap music. Fifteen or twenty years before that, they would have blamed comic books.

But why does it matter what the news people think? It's not like they're actually going to persuade the federal government to ban violent video games. What they might do is try to keep violent video games out of the hands of minors, and if they want to do that, they can go right ahead. They've already been trying that for a long time, though. In theory, minors can't actually buy M-rated games from most stores, because these stores voluntarily enforce rules regarding the ESRB ratings, but most minors have these things called parents, and parents invariably buy video games for their children without even looking at the ratings.

If young, impressionable children playing violent games is indeed a problem, then irresponsible parents are the cause. They buy games like Grand Theft Auto for their 10-year-old kids, and then they turn around and complain when they see how violent the games are. If they educated themselves and paid attention to the ratings, there would be no complaints, because the video game industry is already holding up its own end of the deal. But I guess I shouldn't be surprised that parents ignore ratings, because most parents are old people, and when I say "old people" I'm not talking about age; I'm talking about the fact that they don't know what's going on because they didn't grow up playing video games. As a result, they think video games are just toys, exclusively for children. So they think every video game is appropriate for children, and they're shocked when they find out the truth.

And that's why we have this funny situation in which video games are, according to gaming-illiterate folks, appropriate for no one. If you're an adult and you play video games, they say "you're too old for that!" If you're a kid and you play video games, they say "you're too young for that!" What's the appropriate age?

I say it's any age. There's a video game for everyone.

I think the average adult's completely inadequate understanding of video games is the source of a lot of confusion. They see that Black Ops is the most popular game, so they assume that every game is like Black Ops. But this is just so far from the truth that I don't even know where to start. So I won't start. I'm not even going to waste my time suggesting a list of wholesome and non-violent games for old farts to play in order to broaden their understanding of video games both as an entertainment medium and as a form of artistic expression. They should sit down and find their own way like the rest of us did. It's not hard. All you have to do is look past the mainstream garbage for one second.

Until they do, I'm going to disregard everything they say. Honestly, would you listen to a guy's proposal for a ban on violence in movies if you found out he had never watched a movie in his entire life? Of course not. So why would you listen to a guy talk about violent video games when you know he's never played a video game? I wouldn't, and you really shouldn't.

I haven't written anything new on this stupid blog for the past ten days, so instead I'll just post some additional reading here. Though I don't agree with everything contained within the following articles, I found them somewhat interesting:

Senator Calls for a Study of Video Game Violence

Violence and Video Games in America

The Numbers Behind Video Games and Gun Deaths in America

'Halo 4' Won't Make Your Kids Violent: Why Parents Should Play Video Games With Their Kids

(Wait a minute... why is the best gaming-related journalism coming from a site like Forbes?)

Predictably, in an attempt to make sense of it all, the media and the politicians have come up with a list of scapegoats against which the government is now being pressured to take action. You probably see where I'm going with this. It's the usual list of suspects: gun control, school security, and violence in media — specifically, in video games.

I understand the need to throw the blame around. No one wants to admit that a catastrophe like this one is almost completely unavoidable, so we narrow down the enormous list of contributing factors to an arbitrary few which might, we think, be controlled; we don't even think about the uncontrollable factors because that's just too depressing. So we say, let's tighten security at public schools, and let's tighten restrictions on guns. No one wants to accept that such a mentally disturbed and suicidal person, hell bent on taking people with him when he dies, is going to find a way to do it — even if it's difficult to obtain a firearm, and even if it's not easy to get into the building.

Take a look at this particular shooting, for example. The guy forced his way into a school which had already taken every reasonable security measure. The doors were locked so he shot through a window to get in. Short of multiple armed guards at every entrance (a ridiculously infeasible solution), what were they missing? Metal detectors at the doors, a common placebo in a post-Columbine world, obviously don't help when someone comes in shooting everyone on sight. Maybe bullet-proof glass would have helped, but then he might have crashed his car through the doors, or used a bomb, or waited until the kids went outside for recess. The reality of the situation is that there's no way to make a school impenetrable.

Likewise, there's no realistic way to keep weapons out of the hands of dangerous people. We can try, but there's always going to be another tragedy that occurs despite whatever precautions we take. Bad people are going to get their hands on guns for as long as guns exist — which, by the way, is forever and always, because it's too late to stop them from being invented, manufactured, and sold to millions of people. I could go and steal a gun right now, from a legal gun owner, and kill a guy for no reason, and it will not have mattered what the gun laws were or how the gun's original owner obtained it.

So yeah, blame guns... but be aware that blaming guns only works if your solitary goal is to assign blame. If you actually want to get things done and solve problems, it's pointless. To use a classic (or perhaps trite but still valid) argument, even a total ban on guns would only disarm those civilians who obey the law, and murderers typically don't. Obviously, this is just an example to illustrate the futility of trying to place limits on something for which there's already a black market, and I'm aware that the goal here isn't to repeal the second amendment. Nobody whose opinion is worth a nickle actually wants to ban guns altogether, for then we'd truly be at the mercy of the thugs who still manage to get them. The sensible approach, anti-gun folks say, is to take a careful look at gun regulations and see if they need to be adjusted.

There's a lot of talk about smaller magazines, for example, but reloading isn't that hard, especially when the innocent children you're shooting aren't fighting back. In a perfect world, the ultimate goal of gun regulation would not be to make criminals kill us more slowly, but to keep guns only in the hands of law-abiding citizens. In reality, that's a pretty tough job. Everyone's a law-abiding citizen until his or her first crime, and if that first crime is mass murder then we're boned. If only real life were more like The Minority Report. If only we could know who the criminals are in advance and take away their rights accordingly. But there are some realistic precautions we can take. For example, perhaps the shooter's mother, from whom the guns were stolen, should not have been allowed to have firearms in the same house as a person who was known to be mentally ill. Although I suppose one doesn't always know when ones offspring is crazy enough to shoot up a school, dealing with mental health is probably a good place to start.

And that's what matters, really. The guy was crazy, and we might never know for sure why he did it. Yet, in looking for reason where none exists, politicians have been quick to point instead to a culture obsessed with violence — yes, the culture in which nearly all of us live healthy and functional lives without committing mass murder — and this, of course, is where video games are mentioned. After all, the shooter in Connecticut played video games, according to news reports. That's right, he played violent games, with guns in them, and that must have driven him to kill people... because, as we all know, that's a totally normal reaction to violent video games... and it's not like playing video games is totally normal behavior for an entire generation or two. (In case you missed the sarcasm, what I'm saying is that the killer's possession of violent video games is neither significant nor newsworthy, but that doesn't stop a bunch of technophobic old people from directing a large portion of the blame at the one thing they truly don't understand.)

I shouldn't need to point out that life-long exposure to war-themed, assassination-themed, murder-themed video games (and movies and books) has never given me any desire to kill a bunch of people in real life. But why not? Shouldn't I be going on a killing spree right now? I've killed so many virtual people in video games that, if they were real people, I'd be worse than Hitler. I'm a virtual mass murderer, just like everyone who ever played a first-person shooter. I grew up on shooting things. Even so, I turned out just fine, and I know a few million people who can say the same. Maybe it's because I know the difference between reality and fantasy. Maybe it's because I know the difference between right and wrong, even without the help of some religion to continually threaten me with the idea of eternal damnation. Maybe it's because I'm not mentally ill.

But hey, that doesn't really matter now; conservative politicians and sensationalist newscasters know that video games cause violence, because that's the only explanation for what happened at Sandy Hook Elementary School, right? A crazy guy played video games, and therefore video games made him crazy? Well, that's what we're supposed to believe, but I don't. If someone is evil enough or crazy enough to actually murder 26 people, he certainly doesn't need to play video games in order to get the idea of using a gun as his instrument of death. Furthermore, it's fairly obvious that people who don't play video games are vastly overestimating a first-person shooter's ability to immerse the player. Contrary to what pundits and crackpot psychologists will claim, players are aware that it's only a game and, in the absence of some crippling mental deficiency, they won't be led to believe that really killing real people with a real gun is just as fun and harmless as competing against friends in some crazy deathmatch-style game with cartoon violence and infinite lives.

The shooter played video games just like every other 20-year-old guy I know. There are reports that he was obsessed with them — that he spent all day in his basement playing Call of Duty — but if he truly had a video game addiction (and if such a thing even exists), that's more likely a symptom of his mental illness than a contributing factor. Surely we should all recognize that the act of playing Call of Duty, one of the most popular video game series of the past few years, is not a warning sign that we should hope to use in order to predict school shootings. At least, I certainly hope not. Call of Duty: Black Ops sold 5.6 million copies worldwide in a single day, and 13.7 million copies to date in the United States alone.

That's a whole lot of potential school shootings. If video games create murderers, we should all be soiling our pants and heading for the bomb shelter. Fortunately, the available data doesn't really support the idea that violent video games cause violent acts. (Some further reading here.)

But I'm not too bothered by the blind insistence (regardless of the absence of any reliable evidence) that violence in media is destroying the moral fabric of our society. That's an opinion you're allowed to have, as far as I'm concerned, though I do strongly disagree. What really bothers me is that the people making these claims just don't know anything about video games. If they had pointed solely to the most gruesomely and graphically violent first-person shooters in their quest to find something to blame, then at least their arguments would be coherent. Instead, intentionally or not, the media is once again portraying all of gaming as an amoral pastime for misanthropes, while failing to realize that some of the most popular games of the past decade — I'm looking at you, Portal — simply aren't violent at all.

Things made some sense when they singled out Call of Duty, a game which does, in fact, put players in the role of a soldier who goes around shooting people (though, more accurately, the soldier shoots enemy soldiers in a time of war). But even if they hit the nail on the head, here, I think it was blind luck, since it's pretty clear that most of the people calling for a boycott or a ban on violent games can't even tell one genre from another. Immediately after the shooting, people were so quick to blame Mass Effect — a role-playing game better known for its sex scenes than its shooting — that a mob-like raid on the game's Facebook page began before the real killer was even identified (and ended shortly thereafter).

The media also pointed to StarCraft II, a real-time strategy game, and I think this is especially ridiculous. Not only is this not a mindless murder game; it's not even a shooter. As a strategy game, it's all about resource management, map control, and positioning of troops. Furthermore, StarCraft is to Chess as Call of Duty is to beating your head against the wall. You could judge StarCraft based on the number of virtual "people" who die in a typical match — surely, that number is well into the hundreds, or even thousands — but the player isn't assuming the role of a guy with a gun. The player is the commander telling all the guys with guns where to go. Since real-time strategy games like StarCraft don't put a gun in the player's hands, the experience absolutely does not bear any resemblance to walking into a school and murdering a bunch of children, not even to the sickest mind.

So yes, the game is violent in the sense that its central theme is armed conflict, but it's an idiotic example to use if you're trying to draw some tenuous connection between a mass murder and the killer's enjoyment of interactive media. To some, I guess, the presence of any violent theme is bad enough. But most of these "violent" games, I think, aren't simply violent for the sake of eroding our children's sense of morality. The typical video game has a story, every story involves some form of conflict, the most dramatic conflicts tend to be violent, and violent conflicts in the modern world begin and end with the pull of a trigger. Want fewer war-themed games? Let's have fewer wars. It's not that we should just give up and blame human nature, but we can't expect every video game to be full of super happy rainbows and sunshine either.

Video games consistently imitate life, so even if life does imitate video games on rare occasions, you can't say that video games are the source of all our problems. And, again, it's nothing if not completely illogical to blame video games for a mass murder just because the murderer was one of a billion people who play them. (I bet he also took history classes in high school, but I'm not blaming those history teachers and their lessons about war, because there's no real correlation, let alone any evidence of causation.) There isn't even a very good reason for the news people and the politicians to pick on video games, in particular, so much more than other forms of media that supposedly glorify violence. What about movies and TV shows?

You could say that video games are special because of the level of interactivity that's missing in other forms of entertainment, but I'm beginning to doubt very much that this has anything to do with it. No, video games are special because they're the "new" thing that too many people still don't understand. Fifteen or twenty years ago, they would have blamed rap music. Fifteen or twenty years before that, they would have blamed comic books.

But why does it matter what the news people think? It's not like they're actually going to persuade the federal government to ban violent video games. What they might do is try to keep violent video games out of the hands of minors, and if they want to do that, they can go right ahead. They've already been trying that for a long time, though. In theory, minors can't actually buy M-rated games from most stores, because these stores voluntarily enforce rules regarding the ESRB ratings, but most minors have these things called parents, and parents invariably buy video games for their children without even looking at the ratings.

If young, impressionable children playing violent games is indeed a problem, then irresponsible parents are the cause. They buy games like Grand Theft Auto for their 10-year-old kids, and then they turn around and complain when they see how violent the games are. If they educated themselves and paid attention to the ratings, there would be no complaints, because the video game industry is already holding up its own end of the deal. But I guess I shouldn't be surprised that parents ignore ratings, because most parents are old people, and when I say "old people" I'm not talking about age; I'm talking about the fact that they don't know what's going on because they didn't grow up playing video games. As a result, they think video games are just toys, exclusively for children. So they think every video game is appropriate for children, and they're shocked when they find out the truth.

And that's why we have this funny situation in which video games are, according to gaming-illiterate folks, appropriate for no one. If you're an adult and you play video games, they say "you're too old for that!" If you're a kid and you play video games, they say "you're too young for that!" What's the appropriate age?

I say it's any age. There's a video game for everyone.

I think the average adult's completely inadequate understanding of video games is the source of a lot of confusion. They see that Black Ops is the most popular game, so they assume that every game is like Black Ops. But this is just so far from the truth that I don't even know where to start. So I won't start. I'm not even going to waste my time suggesting a list of wholesome and non-violent games for old farts to play in order to broaden their understanding of video games both as an entertainment medium and as a form of artistic expression. They should sit down and find their own way like the rest of us did. It's not hard. All you have to do is look past the mainstream garbage for one second.

Until they do, I'm going to disregard everything they say. Honestly, would you listen to a guy's proposal for a ban on violence in movies if you found out he had never watched a movie in his entire life? Of course not. So why would you listen to a guy talk about violent video games when you know he's never played a video game? I wouldn't, and you really shouldn't.

Update: December 31, 2012

I haven't written anything new on this stupid blog for the past ten days, so instead I'll just post some additional reading here. Though I don't agree with everything contained within the following articles, I found them somewhat interesting:

Senator Calls for a Study of Video Game Violence

Violence and Video Games in America

The Numbers Behind Video Games and Gun Deaths in America

'Halo 4' Won't Make Your Kids Violent: Why Parents Should Play Video Games With Their Kids

(Wait a minute... why is the best gaming-related journalism coming from a site like Forbes?)

Labels:

call of duty,

grand theft auto,

mass effect,

portal,

starcraft,

violence

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

How To: Steam Offline Mode

Digital distribution and digital rights management are touchy subjects among consumers of video games. The idea that we don't really "own" the software that we buy has been the source of much debate. Many refuse to buy games protected by DRM of any kind, while many more try to avoid downloadable games entirely. Others, meanwhile, have accepted that the way things are going now is the way of the future. And it's okay, mostly. Digital distribution is just too darn convenient and most DRM is only a minor annoyance. (I have to log in? Okay. Wow, that was easy.) Steam, in particular, is often considered an example of digital distribution done right (if there is such a thing), but it still gets a lot of harsh criticism — sometimes for good reasons, and other times because it's cool to hate popular things.

Steam obviously has its perks; the interface is well designed, the features are useful, and the sales aren't bad. The major drawback, though, is that you typically need to be running Steam in order to play a game. (Yes, some games can be launched manually outside of Steam, but others cannot.) Since the Steam client is meant to be used online, it might appear at first glance that you also need to be online in order to play your Steam games. Fortunately, Steam has an "offline mode" to get around that. The problem is that misconceptions about offline mode are widespread and a lot of people don't seem to understand how it works. So let's try it out and see what happens.

Before we start, please note that Steam has its own Offline Mode How-To, which warns that offline mode might stop working if the Steam client is closed improperly (e.g., by shutting down the computer without exiting the program) or if the Steam client is outdated and fails to update (e.g., due to incorrect firewall settings). The rest of Steam's support page consists of step-by-step instructions on how to "configure" offline mode.

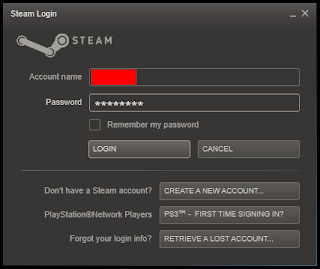

In my opinion, however, these instructions are somewhat misleading. The first step, for example, is to check the "Remember my password" box on the log-in window. As far as I can tell, this step is merely a recommendation and is by no means necessary. If you prefer not to let Steam remember your password at the log-in screen, go ahead and leave this box unchecked as shown below.

For the record, I didn't allow Steam to remember my password while I was testing offline mode for the purpose of writing this post, and everything still worked. (Do note that, while Steam does save account credentials to the computer as a necessary step in configuring offline mode, this is entirely separate from the "Remember my password" feature, which is only meant to save you the trouble of typing your password every time you use Steam online.)

Also somewhat misleading is the way the official guide ends with instructions to restart Steam in offline mode while you're online and signed in. This might be the reason for the widespread misconception that offline mode can only be used if you're already online. Of course, this is not the case. Once configured, Steam will be able to start in offline mode when there's no internet connection without the need to log in immediately beforehand.

Before attempting to use offline mode, you should make sure you haven't explicitly disabled it. You probably haven't — because that would be stupid — but if you have, you'll obviously need to go online to access your account so that you can fix the problem. (If you disabled offline mode and now you have no internet access, you're out of luck. Sorry.)

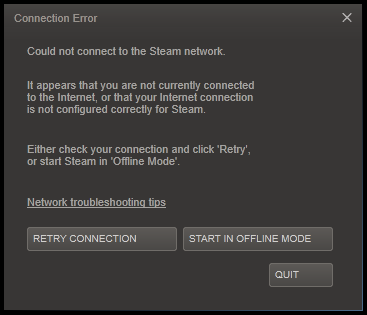

Here's how it works: The use of offline mode requires that Steam be permitted to save account credentials on your computer. If you disallow this and then try to start Steam without any internet connection, the following error message will appear:

To avoid this, we need to make sure that Steam is allowed to save your account credentials. Go online, start up the program and log in, then click on "Steam" in the upper-left corner of the window, and then click on "Settings."

Go to the "Account" tab, and near the bottom of the window, you'll see a check box labeled "Don't save account credentials on this computer."

Having this box checked prevents offline mode from working, so you need to make sure it's unchecked. You probably don't need to worry too much about this feature, since it seems to be unchecked by default, but it's important to know where these options can be found. (Note once again that saving account credentials for offline mode by leaving this box unchecked is not the same as telling Steam to remember your password at the log-in window.)

Obviously, enabling offline mode won't help us if we don't allow our games to finish downloading or updating before we attempt to launch them. Download progress is shown in your Library tab if you're using the "Detail View" or "List View" options (shown below).

There's a total progress bar on the bottom of the Steam window as well.

Clicking the words above that progress bar will show more details for all of your downloads. Before proceeding, you should make sure that all downloads are complete. Otherwise, when you attempt to play a game in offline mode, you might run into this:

At that point, you would have to go back online to finish the installation.

The easiest way to verify that offline mode is enabled — and, in fact, the most foolproof way to use the feature — is to switch to it manually while you're online. Apparently, doing this at least once is also a necessary step in configuring your account for offline play.

Contrary to popular myth, however, this is not the only way to use offline mode. Once everything is set up, you should be able to go straight into offline mode upon launching Steam if your internet connection is down, but I'll get into that later.

To restart in offline mode manually, click "Steam" at the top of the window and then click "Go Offline..."

Then click "Restart in Offline Mode" when the option appears.

Note that this requires account credentials to be saved locally, so you'll have to enable offline mode by giving Steam this permission. If you don't, you'll receive the error message below.

Fortunately, it's a helpful error message; you can just click "Enable Saving Account Credentials" and it will change the setting for you.

Switching to offline mode while online isn't just foolproof. It's arguably more useful, as well, mostly because Steam will remember your preference. If you switch to offline mode manually and then close Steam, you'll be given the option to start in offline mode again next time you launch the application, regardless of whether an internet connection is present.

Under any other circumstances, Steam only offers to start in offline mode if it can't connect to Steam servers. If you prefer offline mode (e.g., because you don't want Steam to track how many hours you play), and you don't want to unplug your computer from the internet completely, then switching manually to offline mode is the way to go.

If we want to get out of offline mode, we can click "Steam" and then "Go Online..."

Then click "Restart and Go Online" when the option appears.

Once Steam restarts, you should be able to log in normally.

After you've checked your settings and downloaded your games — and, in fact, every time you finish using Steam online — you should fully exit the program before shutting down your computer. Failing to do so might cause problems with offline mode.

Do not simply press the little "X" in the upper-right corner of the window. This only closes the window, while the program itself continues to run in the background.

I always close Steam before shutting my computer down, but I recently tried doing it the wrong way, just to see what would happen. After disabling my internet connection and launching Steam, I tried to get into offline mode, and instead I got these two nonsensical error messages:

Fortunately, this is very easily avoided unless your computer is the victim of a power outage. If you're receiving the error messages above, you should close Steam properly next time you're done using it.

Offline mode is enabled, your games are downloaded, you've switched to offline mode at least once, and you've shut down the Steam client. Now, if no internet connection is available next time you try to launch the program, you should be given the option of using offline mode.

When the "Connection Error" dialog box appears, just click "Start in Offline Mode" and Steam will open normally, except that online features like the store and the friends list will (obviously) not work.

Once you're in offline mode, you should be able to run any of your games, provided these games are fully downloaded, installed and updated. (For this example, I've used Portal, which is already installed and ready to play.)

Multiplayer games will run too, but good luck finding any servers.

So what happens if you suddenly lose your internet connection while you're playing? Do you need to enable offline mode in order to prepare for this? Well, not really. Losing your internet connection will not interrupt a single-player game even if offline mode isn't being used. If your connection is okay when you log in, then it doesn't really matter what happens after that.

To demonstrate, I started up Portal while using Steam online, and then disabled my wireless connection. Note the words "No Connection" on the bottom of the Steam window. Steam's online features stopped working but I didn't get kicked out of the game.

There is, therefore, no need to switch to offline mode just because you expect connection interruptions.

So how well does offline mode work? It's not perfect — there are some bugs — but, as far as I can tell at this point, it performs well enough when used correctly.

I've heard plenty of stories of offline mode failing to work for various reasons, most of which are probably related to a firewall-induced failure to update the Steam client, or some other kind of weird scenario which I've been unable to test here.

Specifically, though, I've been told that the locally saved account credentials can expire — in other words, if you haven't logged into Steam in a long time, offline mode might not work anymore — but I won't be able to test for that unless I go some undetermined amount of time without playing any of my multiplayer Steam games, and I don't really feel like doing that. Since most people who play video games have constant internet connections, or at least the ability to log into Steam occasionally, the expiration of saved account credentials should not be a major problem.

I hope this helps.

Steam obviously has its perks; the interface is well designed, the features are useful, and the sales aren't bad. The major drawback, though, is that you typically need to be running Steam in order to play a game. (Yes, some games can be launched manually outside of Steam, but others cannot.) Since the Steam client is meant to be used online, it might appear at first glance that you also need to be online in order to play your Steam games. Fortunately, Steam has an "offline mode" to get around that. The problem is that misconceptions about offline mode are widespread and a lot of people don't seem to understand how it works. So let's try it out and see what happens.

Contents

Preliminary Stuff

Enabling Offline Mode

Making Sure Your Games Are Ready to Play

Switching to Offline Mode While Online

Switching to Online Mode While Offline

Exiting Steam Properly

Launching Steam With No Internet Connection

Lost Connection

The Verdict

Note: This post was last updated in November 2013. Screenshots were taken in July 2012 and might be outdated.

Preliminary Stuff

Enabling Offline Mode

Making Sure Your Games Are Ready to Play

Switching to Offline Mode While Online

Switching to Online Mode While Offline

Exiting Steam Properly

Launching Steam With No Internet Connection

Lost Connection

The Verdict

Note: This post was last updated in November 2013. Screenshots were taken in July 2012 and might be outdated.

Before we start, please note that Steam has its own Offline Mode How-To, which warns that offline mode might stop working if the Steam client is closed improperly (e.g., by shutting down the computer without exiting the program) or if the Steam client is outdated and fails to update (e.g., due to incorrect firewall settings). The rest of Steam's support page consists of step-by-step instructions on how to "configure" offline mode.

In my opinion, however, these instructions are somewhat misleading. The first step, for example, is to check the "Remember my password" box on the log-in window. As far as I can tell, this step is merely a recommendation and is by no means necessary. If you prefer not to let Steam remember your password at the log-in screen, go ahead and leave this box unchecked as shown below.

For the record, I didn't allow Steam to remember my password while I was testing offline mode for the purpose of writing this post, and everything still worked. (Do note that, while Steam does save account credentials to the computer as a necessary step in configuring offline mode, this is entirely separate from the "Remember my password" feature, which is only meant to save you the trouble of typing your password every time you use Steam online.)

Also somewhat misleading is the way the official guide ends with instructions to restart Steam in offline mode while you're online and signed in. This might be the reason for the widespread misconception that offline mode can only be used if you're already online. Of course, this is not the case. Once configured, Steam will be able to start in offline mode when there's no internet connection without the need to log in immediately beforehand.

Before attempting to use offline mode, you should make sure you haven't explicitly disabled it. You probably haven't — because that would be stupid — but if you have, you'll obviously need to go online to access your account so that you can fix the problem. (If you disabled offline mode and now you have no internet access, you're out of luck. Sorry.)

Here's how it works: The use of offline mode requires that Steam be permitted to save account credentials on your computer. If you disallow this and then try to start Steam without any internet connection, the following error message will appear:

To avoid this, we need to make sure that Steam is allowed to save your account credentials. Go online, start up the program and log in, then click on "Steam" in the upper-left corner of the window, and then click on "Settings."

Go to the "Account" tab, and near the bottom of the window, you'll see a check box labeled "Don't save account credentials on this computer."

Having this box checked prevents offline mode from working, so you need to make sure it's unchecked. You probably don't need to worry too much about this feature, since it seems to be unchecked by default, but it's important to know where these options can be found. (Note once again that saving account credentials for offline mode by leaving this box unchecked is not the same as telling Steam to remember your password at the log-in window.)

Obviously, enabling offline mode won't help us if we don't allow our games to finish downloading or updating before we attempt to launch them. Download progress is shown in your Library tab if you're using the "Detail View" or "List View" options (shown below).

There's a total progress bar on the bottom of the Steam window as well.

Clicking the words above that progress bar will show more details for all of your downloads. Before proceeding, you should make sure that all downloads are complete. Otherwise, when you attempt to play a game in offline mode, you might run into this:

At that point, you would have to go back online to finish the installation.

The easiest way to verify that offline mode is enabled — and, in fact, the most foolproof way to use the feature — is to switch to it manually while you're online. Apparently, doing this at least once is also a necessary step in configuring your account for offline play.

Contrary to popular myth, however, this is not the only way to use offline mode. Once everything is set up, you should be able to go straight into offline mode upon launching Steam if your internet connection is down, but I'll get into that later.

To restart in offline mode manually, click "Steam" at the top of the window and then click "Go Offline..."

Then click "Restart in Offline Mode" when the option appears.

Note that this requires account credentials to be saved locally, so you'll have to enable offline mode by giving Steam this permission. If you don't, you'll receive the error message below.

Fortunately, it's a helpful error message; you can just click "Enable Saving Account Credentials" and it will change the setting for you.

Switching to offline mode while online isn't just foolproof. It's arguably more useful, as well, mostly because Steam will remember your preference. If you switch to offline mode manually and then close Steam, you'll be given the option to start in offline mode again next time you launch the application, regardless of whether an internet connection is present.

Under any other circumstances, Steam only offers to start in offline mode if it can't connect to Steam servers. If you prefer offline mode (e.g., because you don't want Steam to track how many hours you play), and you don't want to unplug your computer from the internet completely, then switching manually to offline mode is the way to go.

If we want to get out of offline mode, we can click "Steam" and then "Go Online..."

Then click "Restart and Go Online" when the option appears.

Once Steam restarts, you should be able to log in normally.

After you've checked your settings and downloaded your games — and, in fact, every time you finish using Steam online — you should fully exit the program before shutting down your computer. Failing to do so might cause problems with offline mode.

Note: Valve claimed to have fixed this issue in an August 2012 update. However, as of November 2013, the official Offline Mode How-To still warns that Steam should be closed manually. Failing to follow this step might still cause issues, so I'm leaving this section intact.To properly close the Steam client, click on "Steam" in the upper-left corner of the window, and then click on "Exit." It's that easy.

Do not simply press the little "X" in the upper-right corner of the window. This only closes the window, while the program itself continues to run in the background.

I always close Steam before shutting my computer down, but I recently tried doing it the wrong way, just to see what would happen. After disabling my internet connection and launching Steam, I tried to get into offline mode, and instead I got these two nonsensical error messages:

Fortunately, this is very easily avoided unless your computer is the victim of a power outage. If you're receiving the error messages above, you should close Steam properly next time you're done using it.

Offline mode is enabled, your games are downloaded, you've switched to offline mode at least once, and you've shut down the Steam client. Now, if no internet connection is available next time you try to launch the program, you should be given the option of using offline mode.

When the "Connection Error" dialog box appears, just click "Start in Offline Mode" and Steam will open normally, except that online features like the store and the friends list will (obviously) not work.

Once you're in offline mode, you should be able to run any of your games, provided these games are fully downloaded, installed and updated. (For this example, I've used Portal, which is already installed and ready to play.)

Multiplayer games will run too, but good luck finding any servers.

So what happens if you suddenly lose your internet connection while you're playing? Do you need to enable offline mode in order to prepare for this? Well, not really. Losing your internet connection will not interrupt a single-player game even if offline mode isn't being used. If your connection is okay when you log in, then it doesn't really matter what happens after that.

To demonstrate, I started up Portal while using Steam online, and then disabled my wireless connection. Note the words "No Connection" on the bottom of the Steam window. Steam's online features stopped working but I didn't get kicked out of the game.

There is, therefore, no need to switch to offline mode just because you expect connection interruptions.

So how well does offline mode work? It's not perfect — there are some bugs — but, as far as I can tell at this point, it performs well enough when used correctly.

I've heard plenty of stories of offline mode failing to work for various reasons, most of which are probably related to a firewall-induced failure to update the Steam client, or some other kind of weird scenario which I've been unable to test here.

Specifically, though, I've been told that the locally saved account credentials can expire — in other words, if you haven't logged into Steam in a long time, offline mode might not work anymore — but I won't be able to test for that unless I go some undetermined amount of time without playing any of my multiplayer Steam games, and I don't really feel like doing that. Since most people who play video games have constant internet connections, or at least the ability to log into Steam occasionally, the expiration of saved account credentials should not be a major problem.

I hope this helps.

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

The Moving Portal Paradox

Time for a thought experiment.

Many times, while browsing a certain anonymous imageboard, I've come across the following picture. It's been circulating for a while now, and it still starts a violent debate every time it's posted.

If you've ever played Portal, you probably have some idea of what's going on here. (If you haven't played Portal, you messed up, because it's fun and was given away for free on at least two occasions.) The basic question represented by the image is this: If you have a moving portal (orange) and a stationary portal (blue), and the moving portal engulfs a stationary cube, how does the cube behave when it emerges from the stationary portal? In scenario A, the cube essentially remains stationary as it was before the ordeal. In scenario B, the cube flies out of the blue portal, presumably at the same speed with which the orange portal was moving.

Which scenario is correct? Neither. It obviously can't happen in real life, and it never actually happens in the game. In fact, portals are not typically allowed to exist on moving surfaces, and the only in-game exceptions are scripted events. (This is most likely because moving portals would cause a lot of weird behavior which the game isn't programmed to handle, the above being just one example.) So if you place a portal on a surface in the game, and then that surface moves, the portal vanishes immediately. But what if we simply lifted the seemingly trivial ban on moving portals and conducted a test within the game? Fortunately for us, some guy with a YouTube account created his own test chamber in Portal 2 to find out:

Technical difficulties! It seems that the rule against moving portals isn't the only thing preventing us from doing an experiment. Here it goes again with a faster moving portal:

Clearly, the very game on which this paradox is based just isn't built to handle such a conundrum. However, this is merely a result of the way the game is programmed. It's not an indication of how hypothetical portals might behave, since there's no apparent reason that the portal surface should actually become "solid" as it does in the video above. In short, we've learned nothing. So let's disregard this unfruitful experiment and move on.

The topic has been discussed a few hundred times with no consensus, but I might as well weigh in. I might even be specially qualified to offer some insight, since I do have... um, well... a degree in physics. Okay, okay, so this doesn't make me an expert in the fictional physics of a video game which regularly breaks the actual laws of physics in hilarious ways, nor does it make me an expert in weird scenarios which break the laws of this game, nor does it mean you'll actually think I'm smart (since I've left out, for the sake of privacy, the name of the university which I attended). But at least, unlike most people on the internet, I actually know what momentum is. (Hint: It's not a synonym for inertia.)

So let's take a look at this mess. Initially, the orange portal is moving with respect to the cube. Equivalently, since motion is relative, we can say that the cube is initially moving with respect to the orange portal. However, the cube is initially stationary with respect to the blue portal and, hence, to the room itself. Got it?

Many people look at this scenario and immediately conclude that, if the cube is initially stationary with respect to the room, it should still be stationary with respect to the room afterwards. You know, conservation of energy and conservation of momentum, right? And no apparent forces are acting on the cube, so if it's stationary then it should remain so, right? So option A must be correct... right?

Is this explanation elegantly simple or just crudely simplistic?

This argument in favor of option A is easy to follow, but what bothers me is the assumption that the laws of physics work, and that they work in this particular way.

First of all, how should conservation of momentum work when we're dealing with moving portals, or any portals at all? Even when considering "normal" portal scenarios, in which our two portals are stationary with respect to each other and with respect to the room, this fundamental law of physics seems to fail spectacularly. GLaDOS explicitly tells us that "momentum, a function of mass and velocity, is conserved between portals." I wish I could believe her but, in a strict sense, the law of conservation of linear momentum is already broken in Portal for a very simple reason.

It's important to keep in mind that momentum is a vector; it has both magnitude and direction. We know that direction matters because of the way colliding objects behave. A simple example: Imagine two objects of equal mass, each moving at the same speed, but in opposite directions along the same line. When they collide, the sum of their momenta (initially zero due to the rules of vector addition) must remain unchanged. In an elastic collision, for example, they will bounce off each other and move again in opposite directions at the same speed (and the sum of their momenta will again be zero). In an inelastic collision, they will both stop (in which case it's even easier to see why, together, they have zero momentum). Anyone who paid attention in high school physics, however, will know that they cannot just shoot off in random directions independent of each other, even if their speeds remain the same. If the directions are not right, total linear momentum has not been conserved.

When an object passes through stationary portals in the video game, the magnitude of this object's momentum always remains the same (i.e., the speed is unchanged) with respect to its surroundings. That's good. Unfortunately, the direction of the object's momentum always changes, unless the portals lie on parallel planes and face opposite directions (a very special case). This change in direction is, in fact, a change in momentum, and there is no apparent collision which causes the momentum of another object to change in a reciprocal manner, so conservation is violated. It should be clear now that we cannot blindly apply this particular law of physics to any portal-related problem... at least, not in the most intuitive way. (At least GLaDOS got one thing right: "In layman's terms: speedy thing goes in, speedy thing comes out.")

When an object passes through stationary portals in the video game, the magnitude of this object's momentum always remains the same (i.e., the speed is unchanged) with respect to its surroundings. That's good. Unfortunately, the direction of the object's momentum always changes, unless the portals lie on parallel planes and face opposite directions (a very special case). This change in direction is, in fact, a change in momentum, and there is no apparent collision which causes the momentum of another object to change in a reciprocal manner, so conservation is violated. It should be clear now that we cannot blindly apply this particular law of physics to any portal-related problem... at least, not in the most intuitive way. (At least GLaDOS got one thing right: "In layman's terms: speedy thing goes in, speedy thing comes out.")

So the law of conservation of linear momentum is out. But can we at least assume that some of Newton's laws are satisfied? Going back to our original thought experiment, there doesn't seem to be any external force acting on the cube, and therefore its velocity should remain zero, right? After all, according to Newton's first law, an object at rest should remain at rest in the absence of any force.

But Newton also said that an object in motion should keep moving in a straight line until acted upon by some force. We've already seen that an object passing from one portal to another will often see a change in direction, so unless we can identify the force responsible for this, Newton's first law appears to be broken. We encounter a similar problem if we look at the "F=ma" form of Newton's second law. The equation tells us that, if the net force is zero and the cube's mass is nonzero, the cube's acceleration should be zero. However, it appears that the acceleration of a cube passing through portals is never zero unless we've been restricted to that special case of two portals on parallel planes facing opposite directions.

But Newton also said that an object in motion should keep moving in a straight line until acted upon by some force. We've already seen that an object passing from one portal to another will often see a change in direction, so unless we can identify the force responsible for this, Newton's first law appears to be broken. We encounter a similar problem if we look at the "F=ma" form of Newton's second law. The equation tells us that, if the net force is zero and the cube's mass is nonzero, the cube's acceleration should be zero. However, it appears that the acceleration of a cube passing through portals is never zero unless we've been restricted to that special case of two portals on parallel planes facing opposite directions.

Acceleration is a change in velocity, and velocity (like momentum) is a vector with both magnitude and direction. If a moving object changes its direction, this counts as acceleration, even if the magnitude of the velocity (i.e., the speed) in a given reference frame remains unchanged. Therefore, an object changing direction as a result of passing through portals must have accelerated. According to Newton's second law, this acceleration would suggest the presence of some force. So should we assume that portals can exert a force on objects passing through them and that this force always accelerates an object such that its direction is changed but its speed remains constant? We could, but it's not a very satisfying answer. Since we don't know anything about this made-up force aside from the fact that one interpretation of our thought experiment suggests that such a force might be convenient, it doesn't really help us solve the problem in a meaningful way. Rather than making more assumptions to justify things that don't quite fit, we should be throwing out the dubious assumption that Newton's first and second laws are applicable to any problem involving portals in the first place.

Finally, what of conservation of energy? Does this law really apply in such a totally nonsensical and impossible scenario? You'd have a hard time arguing that it does because, once again, the law doesn't seem to apply to portals in general (let alone our weird moving portal problem). Any two portals at differing heights will essentially cause a change in the gravitational potential energy of a transported object without a corresponding change in kinetic energy (or any other energy we can see). Furthermore, if you place one portal directly above another, an object falling out of one and into the other will gain greater and greater kinetic energy with each pass, and the only thing that will stop this never-ending increase in kinetic energy is air resistance. Energy comes from nowhere, and this isn't something that happens when energy is being conserved.

Finally, what of conservation of energy? Does this law really apply in such a totally nonsensical and impossible scenario? You'd have a hard time arguing that it does because, once again, the law doesn't seem to apply to portals in general (let alone our weird moving portal problem). Any two portals at differing heights will essentially cause a change in the gravitational potential energy of a transported object without a corresponding change in kinetic energy (or any other energy we can see). Furthermore, if you place one portal directly above another, an object falling out of one and into the other will gain greater and greater kinetic energy with each pass, and the only thing that will stop this never-ending increase in kinetic energy is air resistance. Energy comes from nowhere, and this isn't something that happens when energy is being conserved.

Again, you could always assume that the portals are allowed to add or subtract exactly the appropriate amount of energy to account for this, perhaps drawing from a near-infinite and invisible source, but to allow such an assumption would be to throw all systematic and logical approaches to the problem out the window. It's a cop out, and it doesn't provide us with a means by which to proceed with this thought experiment. We might as well assume that portals are made of cheese and that they're powered by the souls of orphans. Instead of resorting to magical explanations, it's a lot easier to make no assumptions at all and simply concede that conservation of energy is a concept better left in the real world.

To make a long story short, the commonly cited laws of physics don't seem to be applicable to portals, regardless of whether the portals are moving or stationary. If they do apply, they don't seem to work in the most obvious way. So how do we even begin to make any sense out of the weird moving-portal example in question? Well, I have my own idea; you don't have to agree with it.

What I want to point out first is that a change in direction as seen by an outside observer is not actually a change in direction as experienced by the object which moves through a pair of portals. After all that fuss about how changes in direction are so important, it probably looks like I'm contradicting myself a little bit, but hear me out. First consider the regular portal scenario with two stationary portals.

Think about what you see if you look directly into a portal as an object passes through it. Since light passes through portals the same way as everything else does, you can easily see that the object appears to move in a straight line! Anyone who played the game should be familiar with this. Furthermore, if you jump into one of the portals yourself, there's no immediate indication, in this first-person perspective, that a change in direction has occurred, even though a third-person observer would disagree. To the portal traveler, it's just like going through a doorway. A person passing through portals would probably not "feel" a change in direction, or any kind of acceleration, even though acceleration due to a directional change technically has occurred.

So perhaps we can say that the direction of an object's velocity remains constant with respect to the portal system reference frame. To make this claim, we have to take the portal concept seriously and invent a new frame of reference and coordinate system in which both portals occupy the same space at all times. It's goofy, but it seems to work... and by "seems to work" I mean it's the only way our portal system can truly conserve momentum, magnitude and direction included. We can see clearly in the game that if an object enters one portal at a certain angle, it actually emerges from the other portal at the same angle, but only if each angle is measured relative to each respective portal.

In other words, if you go straight into one portal, you come straight out of the other; if you hit one portal at a 73° angle, you come out of the other portal at a 73° angle. Your journey through the portal system might have changed your course from, say, west to north, but if we stop trying to measure all of our angles relative to some universal coordinate system (e.g., the room) and just measure from the surface of the nearest portal, the troublesome change in direction is suddenly less troublesome. Mathematically, it's no longer there. So maybe GLaDOS was right after all; maybe we just need to ignore the outside observer and trust the portal traveler instead.

Now let's go back to the moving portal example. Things make a bit more sense when we use this new frame of reference and measure everything with respect to the nearest portal. If the direction of a moving object with respect to this "portal system reference frame" remains unchanged as the object passes through (and we can see that this is the case), it's not so crazy to say that the speed of the object, with respect to the nearest portal, might remain the same as well. Maybe both the direction and magnitude of an object's velocity should remain constant, but only with respect to the "portal system reference frame" and not with respect to anything else.